Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS | More

This week in space news

China in space: The Chinese Space Agency has sent a trio of astronauts to spend the next three months of the Tiangong space station. This is a brand new modular space station built and operated by China and they arrived on a Chinese spaceship sent up on a Chinese-made rocket.

The Chinese and Russian space agencies will also work together to begin construction of a base on the surface of the moon in 2026, due for completion by 2036 – but they won’t be sending astronauts until after it is fully operation and the robots have had a chance to explore.

Boeing boeing … going? NASA is working with Boeing on sending the Starliner crew capsule into space for another test this July. Starliner was originally due to be operational, ferrying crew to the ISS last year, working alongside the SpaceX Crew Dragon, but it has been hit by problems.

For the new test Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket without a crew on board. IF it goes to plan the first crewed mission could be towards the end of this year with astronauts Barry Wilmore, Nicole Mann and Mike Fincke on board.

Betelgeuse had gas! The red supergiant star betelgeuse, found on the shoulder of the hunter in Orion’s Belt, which began mysteriously dimming last year was just being blocked by a cloud of gas and dust, according to a new study.

Astronomers from France created a computer simulation based on images from the Very Large Telescope in Chile to determine the Great Dimming was caused by the star ejecting a bubble of gas and giant blobs of plasma moving on its surface.

The temperature drop from the giant blobs led to the creation of an opaque dust which dimmed its appearance when viewed from Earth.

Making space sustainable: The World Economic Forum has launched a new Space Sustainability Rating, designed to shed light ont he problem of space junk and the impact it is having on our orbital evnironment.

The argument is that it is a problem one single government can’t solve, with rules and enforcement from multile nations required to solve the problem.

It will work like nutrition and energy efficiency labels, making it clear what companies and organisations are doing to improve the near-Earthenvironment.

In other news: NASA has a new deputy administrator, after former astronaut Pam Pelroy was confirmed by the senate, and the opportunity to apply to be a European Space Agency astronaut has passed. The deadline for entries closed on Friday June 18th.

Launches this week

June 24: Launch site: SLC-40, Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida – A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket will launch the Transporter 2 mission, a rideshare flight to a sun-synchronous orbit with numerous small microsatellites and nanosatellites for commercial and government customers. Moved up from July.

June 25: Launch site: Plesetsk Cosmodrome, Oblast, Russia – A Roscosmos Soyuz 21.b will send a Russian military intelligence ELINT satellite into heliosynchronous orbit.

Exoplanet of the week

HD 209458 b (nickname “Osiris”)

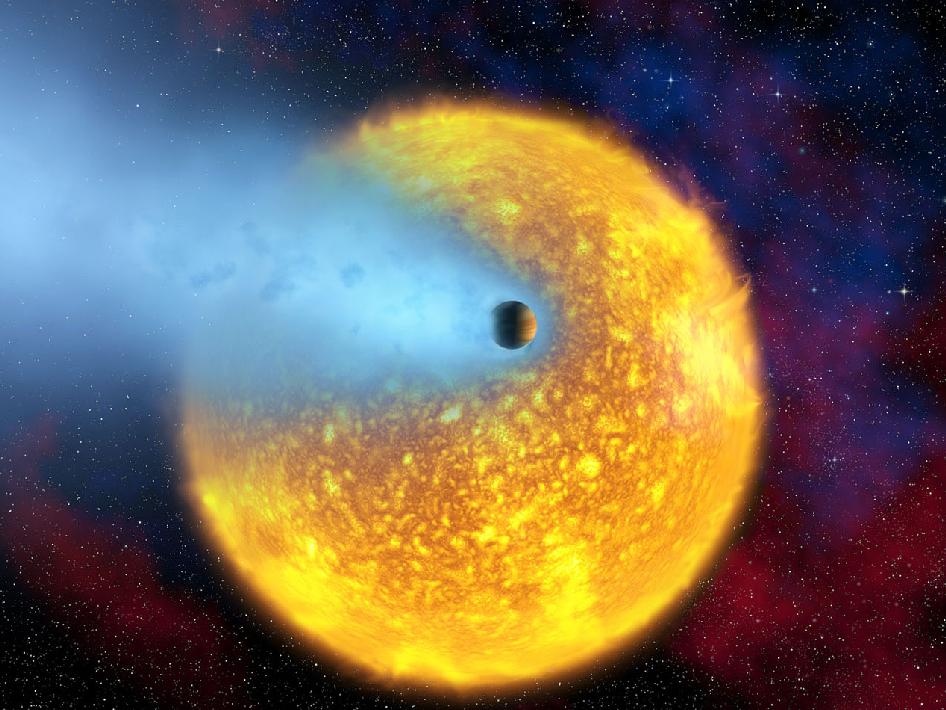

The first planet to be seen in transit (crossing its star) and the first planet to have it light directly detected. The HD 209458 b transit discovery showed that transit observations were feasible and opened up an entire new realm of exoplanet characterization.

The planet is 1.3 times larger than Jupiter, or about 220 times the size of the Earth in terms of mass. It orbits very very close to its star – just one eight that of Mercury around the Sun – going around its star every 3.5 days.

That means a year on Osiris is just 3.5 Earth days – meaning you’d have over 100 birthdays per Earth year if you somehow managed to live on the strange hot world.

Although given it is a gas giant, based on both the high mass and volume, there wouldn’t be much of a surface to stand on if you did visit.

It belongs to a type of extrasolar planet known as ‘hot Jupiters’ – Giant, gaseous planets in low orbits – with a surface temperature more than twice that of Venus – at a whopping 1,000 degrees Celsius.

It’s about 150 light years from Earth and the parent star is a 8th magnitude G-type main sequence star slightly larger than the Sun found in the constellation of Pegasus and visible with a good small telescope.

If you want to try and find it:

| Right ascension | 22h 03m 10.7728s |

|---|---|

| Declination | +18° 53′ 03.550″ |

The planet was first discovered in 1999 and shot to fame in 2009 after astronomers announced ‘water vapour’ in the atmosphere – with follow up studies suggesting it is an example of a ‘carbon planet’.

On 23 June 2010, astronomers announced they have measured a superstorm (with windspeeds of up to 7000 km/h) for the first time in the atmosphere of Osiris, which has extremely hot day side and a cooler night side.

It was the first planeetary atmosphere outside the solar system ot be measured, and by 2004 astronomers found an enourmous envelope of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen around the planet reaching temperatures of 10,000 Kelvin.

The exosphere goes out as far as three times the radius of Jupiter, suggesting hte planet oculd be losing up to 500 million kg of hydrogen per second. It is thought this could be common among planets orbiting Sun-like stars closer than 0.1 AU.

Its ionised magnetic field may prevent all the atmosphere from disappearing. A 2009 study found evidence of water vapour, carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere, refined in 2021 to reveal water vapour, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, methane, ammonia and acetylene.

These are consistent with high carbon levels and suggest it may be a prime example of a ‘carbon planet‘.

Features

Each week we expand on a number of big news stories and explore some major astronomical discoveries. This includes the latest in space science, tech and research.

This is the features section of the podcast. From the latest NASA initiatives to cutting edge space science. We will explore the ideas through interviews, audio from official sources and traditional broadcast journalism.

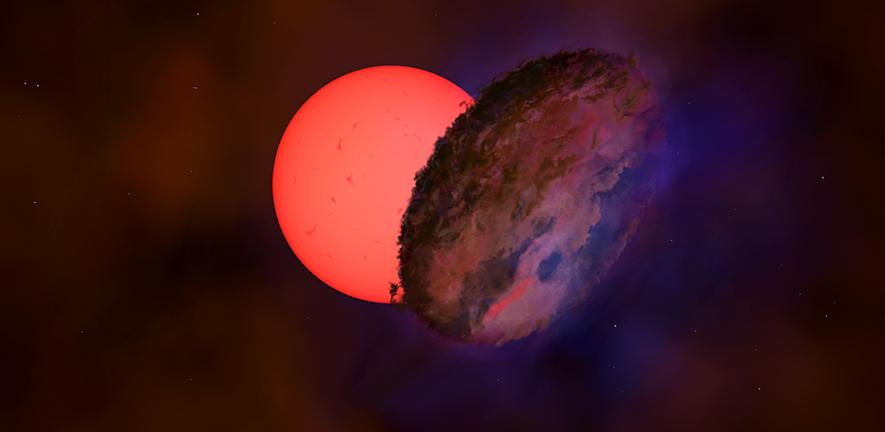

A large star called What is That?

VVV-WIT-08, or the ‘large star that blinked’ was a serendipitous discovery by an international team of astronomers led by Leigh C Smith from the University of Cambridge.

They found that the star decreased in brightness by a factor of 30 – to the point it almost disappeared from the sky. Stars commonly pulsate or are eclipse by another star in a binary system, but this one ‘blinked’ for months before brightening again.

Found some 25,000 light years away from Earth near the galactic centre, VVV-WIT-08 may belong to a new class of ‘blinking giant’ star found in a binary system.

It is 100 times larger than the Sun and is eclipsed by another stellar object every few decades – this is a companion object in a shared orbit, or within its orbit we have yet to discover.

This could be nother star or a very large planet surrounded by a disc of dust that covered the giant star. When viewed from the Earth this would have the effect of causing it to disappear then reappear – or ‘blink’.

“It’s amazing that we just observed a dark, large and elongated object pass between us and the distant star and we can only speculate what its origin is,” said co-author Dr Sergey Koposov from the University of Edinburgh.

They used computer modelling to determine whether this object was something else within the heavily populated central region of the Milky Way – rather than something in a shared orbit with the giant star.

However, simulations showed that there would have to be an implausibly large number of dark bodies floating around the Galaxy for this scenario to be likely.

One other star system of this sort has been known for a long time. The giant star Epsilon Aurigae is partly eclipsed by a huge disc of dust every 27 years, but only dims by about 50%.

There are certainly more to be found, but the challenge now is in figuring out what the hidden companions are, and how they came to be surrounded by discs, despite orbiting so far from the giant star

Leigh Smith

A second example, TYC 2505-672-1, was found a few years ago, and holds the current record for the eclipsing binary star system with the longest orbital period ⎼ 69 years ⎼ a record for which VVV-WIT-08 is currently a contender.

VVV-WIT-08 was found by the VISTA Variables in the Via Lactea survey (VVV), a project using the British-built VISTA telescope in Chile and operated by the European Southern Observatory, that has been observing the same one billion stars for nearly a decade to search for examples with varying brightness in the infrared part of the spectrum.

Project co-leader Professor Philip Lucas from the University of Hertfordshire said, “Occasionally we find variable stars that don’t fit into any established category, which we call ‘what-is-this?’, or ‘WIT’ objects.

“We really don’t know how these blinking giants came to be. It’s exciting to see such discoveries from VVV after so many years planning and gathering the data.”

There now appear to be around half a dozen potential known star systems of this type, containing giant stars and large opaque discs.

“There are certainly more to be found, but the challenge now is in figuring out what the hidden companions are, and how they came to be surrounded by discs, despite orbiting so far from the giant star,” said Smith. “In doing so, we might learn something new about how these kinds of systems evolve.”

Reference:

Leigh C Smith et al. ‘VVV-WIT-08: the giant star that blinked.’ Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab1211

China in space

The Chinese space agency has sent a trio of astronauts up to their new station, named Tiangong, where they will stay for the next three months and prepare the facility for the next two modules.

It is significantly smaller than the ISS, with just 1,700 cubic feet of living space compared to more than 11,000 cubic feet of space for humans on the ISS.

There will be 11 trips, including four with a crew to the station over the coming two years to finish construction, including launching the final two research modules.

When complete, Tiangong will have a total of three modules, making it closer to the Soviet-era Mir station than the ISS, which has 16 modules run by different nations.

Russia and China going to the moon: China has signed a memorandum of understanding, and outlined a timetable with Russia for a joint base on the surface of the Moon – due to begin construction in 2026.

Tiangong is currently expected to out live the ISS, as it is scheduled to operate until at least 2031, and possibly longer.

The first module for Tiangong is the Tianhe, which is the primary living quarters for the new Chinese station.

This will be joined by Wentian and Mengtian, two laboratory modules due to launch next year.

This was China’s third space station, although this is the first to incorporate a modular design, similar to, but much smaller than the International Space Station.

Some of the 11 launches will be robotic and automated missions to place aspects of the station in orbit, others will be crewed to have astronauts install the modules.

Once the entire station is complete, it is expected that future missions will be purely scientific, similar to those of the International Space Station.

Much like the ISS, China is also expected to invite other nations to take part or send astronauts as part of the small crew.

This happened with Mir space station, that saw British astronaut Helen Sharman spend time on the station with two Russian cosmonauts.

Mission commander Nie Haisheng, 56, and fellow astronauts Liu Boming, 54, and Tang Hongbo, 45, are former People’s Liberation Army Air Force pilots with graduate degrees and strong scientific backgrounds.

All Chinese astronauts so far have been recruited from the military, underscoring its close ties to the space program.

Boeing, Boeing Going?

Boeing will send an uncrewed Starliner into space next month, with the hope of sending a crewed capsule up into orbit by the end of the year, according to NASA.

This follows a rocky year for the aviation firm, whose Starliner capsule was beset with technical problems preventing it from joining the SpaceX Crew Dragon in ferrying astronauts to the ISS last year.

Teams inside the Starliner production factory at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida recently began fueling the Starliner crew module and service module in preparation for launch of Orbital Flight Test-2 (OFT-2) at 2:53 p.m. EDT on Friday, July 30.

The fueling operations are expected to complete this week as teams load propellant inside the facility’s Hazardous Processing Area and perform final spacecraft checks.

Once fueling operations are complete, teams from Boeing and United Launch Alliance (ULA) will prepare to transport Starliner to the Vertical Integration Facility (VIF) at Space Launch Complex-41 on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station for mating with ULA’s Atlas V rocket.

In preparation for Starliner’s next flight, NASA and Boeing have closed all actions recommended by the joint NASA-Boeing Independent Review Team, which was formed as a result of Starliner’s first test flight in December 2019.

The review team’s recommendations included items relating to integrated testing and simulations, processes and operational improvements, software requirements, crew module communication system improvements, and organizational changes.

Boeing has implemented all recommendations, even those that were not mandatory, ahead of Starliner’s upcoming flight.

During the OFT-2 mission, Starliner will test its unique vision-based navigation system to autonomously dock with the space station and deliver approximately 440 pounds, or roughly 200 kilograms, of cargo and crew supplies for NASA. Starliner is expected to spend five to 10 days in orbit before undocking and returning to Earth, touching down on land in the western United States.

Providing Starliner’s second uncrewed mission meets all necessary objectives, NASA and Boeing will look for opportunities toward the end of this year to fly Starliner’s first crewed mission, the Crew Flight Test (CFT), to the space station with NASA astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore, Nicole Mann, and Mike Fincke on board.

NASA’s Commercial Crew Program is working with industry through a public-private partnership to provide safe, reliable, and cost-effective transportation to and from the International Space Station, which will allow for additional research time and will increase the opportunity for discovery aboard humanity’s testbed for exploration.

The space station remains the springboard to space exploration, including future missions to the Moon and eventually to Mars.

How will astronauts live on the Moon?

ICON, a developer of advanced construction technologies including robotics, software and building materials, partnered with SEArch+ to work with NASA on the development of a space-based construction system to support future exploration of the Moon.

SEArch+’s design for ICON’s Project Olympus, is a sustainable outpost consisting of habitats, sheds, landing pads, blast walls, and roadways.

“The Lunar Lantern” aims to exceed the factors of safety for its inhabitants in support of mankind’s first extended mission on the Moon’s surface.

It fits within the wider NASA Artemis goal of ensuring a sustainable and sustained human presence on the moon once astronauts return in 2024 on Artemis 3.

The main habitat of the Lunar Lantern would include three structural components – a base isolator, tension cables and a whipple shield. These would act as seismic dampeners to absorb shocks from moonquakes.

The shield will act to protect inhabitants from micrometeorites, extreme heat and solar radiation. There will also be landing pads for rockets – possibly the SpaceX Lunar Starship, roadways, blast walls and more.

NASA won’t be the only nation sending astronauts to the Moon, although they will likely get there next. China and Russia have outlined their timetable for future lunar missions, including a new base on the surface that will begin construction in 2026 and finish by 2036.

No responses yet