I’ve had an idea floating around in my head for a few years now. The concept involves human evolution, space and the impact super powers emerging in one generation might impact the world.

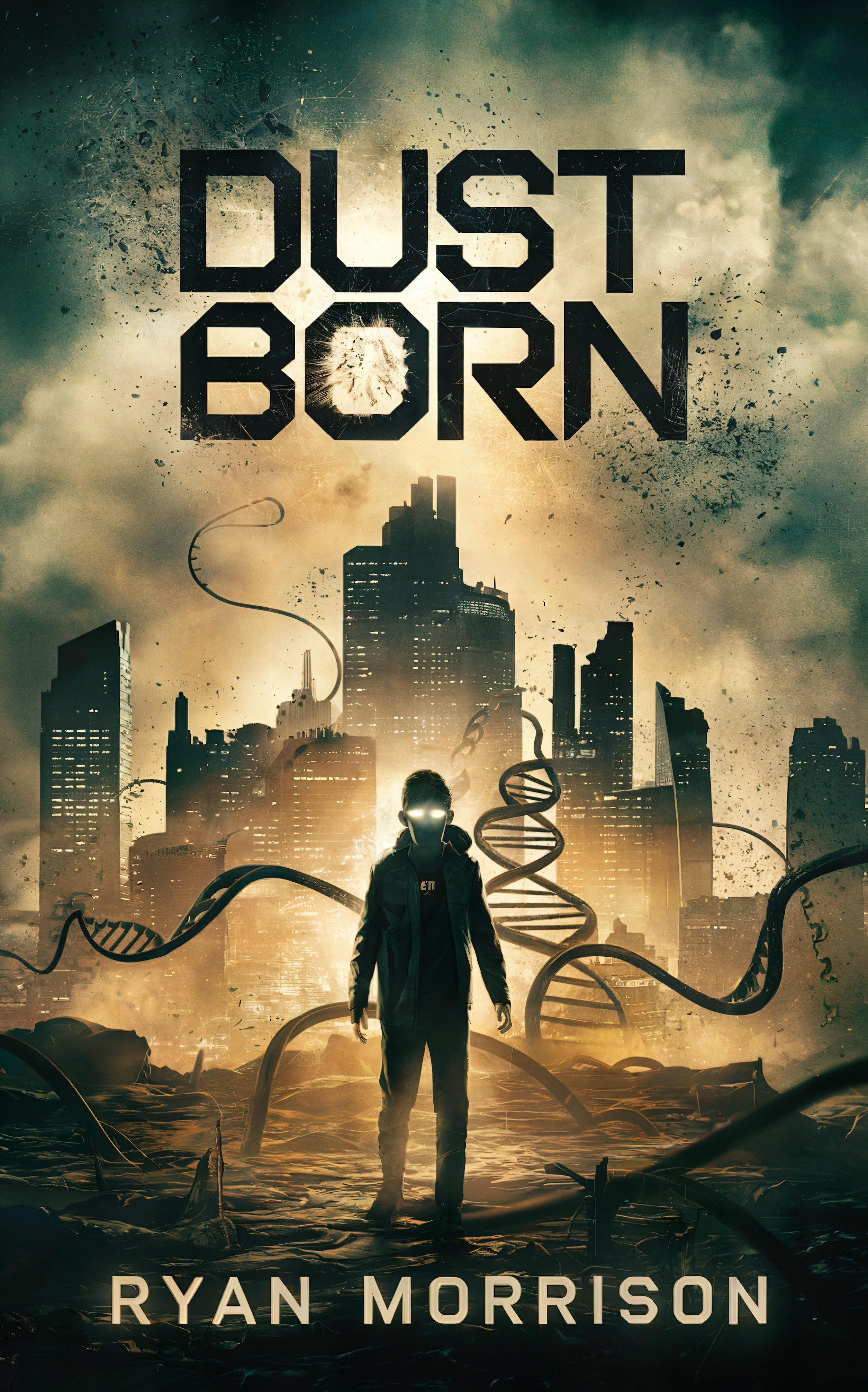

This finally came to fruition in the form of Dustborn, a relatively short novel focusing on Adrian “Ade” West, an 18-year-old Dustborn telepath living in a gritty, divided London of 2025. But what are the Dustborn? They are a cohort of teenagers born 18 years ago while Earth passed through a rare, once in 300,000 year space dust cloud.

Writing Dustborn was an exhilarating, and sometimes overwhelming, journey into the unknown. As a journalist with more than two decades experience, I’ve always been fascinated by humanity’s pivotal moments — those leaps forward that define who we are and where we’re going.

The process of writing this book wasn’t just about telling a story; it was about creating a living, breathing world. It was about digging into the “what ifs” of human evolution, asking hard questions about societal tension, and building characters who could navigate this world in a way that felt real.

How Duststorm came about

The foundation of Dustborn came from a single, vivid image that stuck in my mind: Earth passing through a shimmering cosmic dust cloud. What if this dust wasn’t just inert particles but something ancient and purposeful, triggering a transformation in human DNA? That idea hooked me immediately. It was both grounded in scientific plausibility and rich with dramatic potential. I spent weeks researching everything from interstellar dust to epigenetics to better understand how such an event might work and what its effects could be.

Once I had the central conceit, I needed to define its rules. When does the dust take effect? Who does it affect? I decided it would only alter the DNA of unborn children, creating a “generation” that would begin to reveal their abilities in early childhood. That decision anchored the timeline: the dust cloud passed Earth in 2007, the first Dustborn children started showing powers around 2011, and by the story’s start in 2025, they’re teenagers or young adults. That gave me a window to explore not just their lives, but how the world reacted to them over time.

I also explored whether this dust cloud had passed by Earth previously and set it that the last time was 300,000 years ago, leading to the immergence of human sentience and the first homo sapiens.

Who gets powers?

From there, I built out the powers themselves. I didn’t want these abilities to feel like superhero tropes. They needed to be tied to the natural world—like manipulating light, telekinesis, or altering sound waves—but with limits that would create tension. For example, a pyrokinetic’s power burns them from the inside if they lose control, and a telepath risks psychic overload. These limitations became just as important as the powers themselves, because they shaped how the characters interacted with their gifts—and the world around them.

Once I had the rules of the dust and the powers, I had to tackle the world. How would governments, corporations, and ordinary people respond to the Dustborn generation? This was where the story became a reflection of our own world. I drew from real-world examples of societal tension: how we respond to change, fear what we don’t understand, and sometimes exploit what we see as “different.”

In Dustborn, the government forms the Orion Bureau to monitor, train, and control the Dustborn. But the Bureau is far from a monolith of good or evil—it’s a reflection of humanity’s dual instincts for order and fear. Some agents genuinely want to help, while others see the Dustborn as tools to be weaponized. Writing the Bureau’s policies, protocols, and moral ambiguity was like sketching the bones of a new institution. I wanted their methods to feel plausible—an uneasy mix of compassion and control.

Meanwhile, society itself became a character in the story. Dustborn kids are seen as miracles by some and monsters by others. There are protests, debates, and even graffiti scrawled across walls: NO DUST FREAKS. These details helped the world feel textured, like a real place grappling with a seismic shift.

The characters came next, and they were where the story truly came alive for me. Adrian “Ade” West, the protagonist, started as a quiet teenager with an overwhelming burden: telepathy. I didn’t want him to be a traditional hero. Ade is reluctant, even afraid of his power. He’s not trying to save the world—he’s just trying to survive it. But that vulnerability made him the perfect lens through which to explore the Dustborn experience. As he’s pulled deeper into the Bureau’s orbit, he starts to realize the cost of ignoring his potential

Each supporting character brought a new angle to the story. Keisha, who manipulates light, struggles with the weight of being viewed as extraordinary while feeling deeply flawed inside. Logan, a wind manipulator, hides his fears behind a brash exterior but secretly longs for control in a chaotic world. Imani, who manipulates sound waves, is both a calming presence and the group’s moral compass. And Peter, with his shaky telekinesis, is deeply self-conscious about whether he’ll ever live up to what’s expected of him. Together, they formed a cast that felt like real people—not just a team, but a group of individuals with their own fears, desires, and conflicts.

I spent time refining their backstories, sketching out how the dust cloud affected their families, their childhoods, and their relationships. For instance, Ade’s telepathy isn’t just a tool—it’s a source of deep trauma. He accidentally overhears people’s darkest thoughts, which isolates him even further in a world where he already feels like an outsider. These personal struggles gave each character stakes beyond the external conflicts.

Crafting the plot was where everything finally came together. The core of Dustborn became a tug-of-war between control and freedom, both for the Dustborn as a group and for Ade as an individual. The Orion Bureau serves as both a guide and an oppressor, pulling Ade into their pilot program with promises of stability and training. But as he learns more, he begins to question their true motives—especially when he encounters Nova Dawn, a rebel faction fighting to free the Dustborn from the Bureau’s grip.

The interplay between the Bureau and Nova Dawn was one of my favorite parts to write. Neither side is purely good or evil. The Bureau provides order but at great personal cost to the Dustborn they oversee. Nova Dawn offers freedom but with methods that sometimes border on dangerous vigilantism. Ade and his friends are caught in the middle, forced to navigate moral gray areas while trying to find a path that feels right.

Writing the meltdowns—the catastrophic moments when a Dustborn loses control of their power—was perhaps the most intense part of the process. Each meltdown became a metaphor for what happens when we suppress emotions too long or when we’re pushed beyond our limits. These scenes weren’t just action set pieces; they were deeply emotional moments where characters had to confront their own fears and vulnerabilities.

One of the most rewarding aspects of writing Dustborn was watching the world grow more complex with every draft. What started as a simple question—What if human evolution took a cosmic leap?—became a sprawling narrative about power, identity, and belonging. The rules I built early on gave the story structure, but the characters gave it heart. They surprised me, frustrated me, and ultimately made the journey worth every sleepless night.

Now, as I look back, I realize Dustborn is as much about the process of writing as it is about the story itself. It’s about asking “what if” and daring to follow the answer, no matter how strange or challenging it might be. For me, this book became a reminder that evolution—whether cosmic or personal—is messy, unpredictable, and beautiful in its imperfection. And that’s where the best stories come from.

The novel will be available as an eBook and Paperback through Amazon (self-published). I’ll also be releasing the audiobook chapter-by-chapter through a podcast.

2 Responses

I like the sound of this, please can you let me know how to subscribe to the podcast and when the ebook will be available?

Thanks

Will do. You can listen to chapter one at the bottom of the post. I’ll add a download link while I work on the podcast.